The price our native rice grains pay in the rush for a bigger and better yield

RINCHEN DORJI

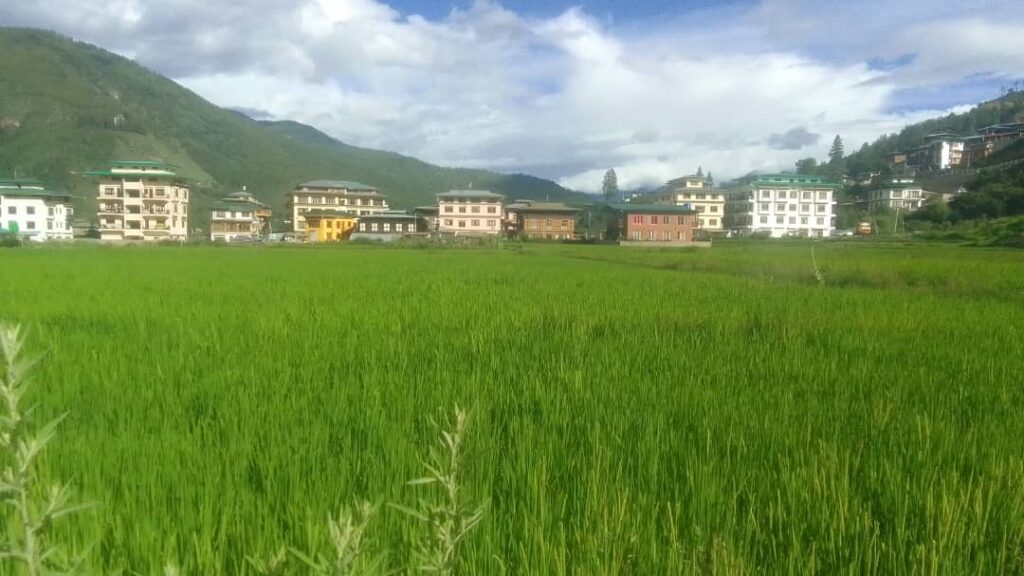

Paro

Not long ago, when a pot of native E‑chhum or introduced Japan Rice used to simmer in kitchens across Paro, the entire valley would awaken to its irresistible scent.

Neighbors would lean over walls to ask, “Which rice are you cooking? I can smell it from here.”

Elderly farmers still recall those mornings. “When that brown‑rice cooked, the scent reached every courtyard,” says their smiling memory.

But today, even in Paro’s lush terraced fields, once the loci of those fragrant mornings, those aromas are all but gone. The grains no longer sing with fragrance and the cooking lacks that characteristic whisper of earth and memory.

This is not a tale of shrinking yields. Over 2018–2022, as per statistics from the ministry of agriculture, Paro has consistently recorded irrigated paddy yields averaging 5.9 tonnes per hectare, or 2.37 tons per acre, well above the global average of roughly 4.25 t/ha.

But in pursuit of quantity, quality has slipped. Notably the aroma and texture that defined E‑chhum and Japan Rice until the late 1990s.

That fragrant rice of the past

From time immemorial and up unto the late 1980s and early 1990s, Paro’s rice was as renowned for its scent as for its yield. According to National Environment Commission reports, rice production in Bhutan rose sharply between 1989 and 1997—a 58 percent jump

Farmers planted native long‑grained brown rice (E‑chhum) and the introduced Japan variety, both tall, low‑yielding—but rich in aroma and resistant to exotic pests of that era.

Elders describe waking before dawn to the scent of rice dancing in the hearth. The aromas carried on the morning breeze, greeting the day. But those days are fading fast.

The shift

From the late 1990s onward, Bhutan’s Department of Agriculture promoted high‑yielding varieties (HYV), short‑duration and climate-resilient.

By 2022, HYV adoption rate nationwide had reached about 52 percent, up from roughly 35 percent in 2004. In Paro specifically, experts estimate adoption above 85 percent of total paddy acreage

These modern varieties, paired with inorganic fertilizers and pre‑emergent herbicides like butachlor boosted yields but, over time, also degraded soil ecology.

“The new rice grows fast and fills the pan hard,” says Passa Gyem of Lango gewog.

“But when we cook it, the scent and the joy is missing.”

A few fields still grow patches of traditional brown E‑chhum, but even those grains no longer release that old perfume.

“We feel cheated,” adds Chencho from Geptey. “There is no greeting scent when the rice cooks. It’s just white steam,” he says.

Facts across Bhutan

Prior to the 1990s, traditional varieties yielded perhaps 1.5 t/acre, a figure not high, but steady, and aromatic. From 1989–97 Bhutan’s program raised yields national average from 44,000 t to nearly 74,720 t.

In Paro, yields crept above global averages by 2018, reaching around 2.37 t/acre by 2022. Yet at the same time, farmers lament the absence of aroma and texture once unmistakable.

Farmers report erratic rainfall, delayed monsoons, or untimely rains during harvest, and diminishing glacial‑fed spring water flow which are all tied to changing climate patterns

According to climate‑agriculture studies, small shifts in temperature and precipitation directly impact rice yields and grain quality by affecting grain‑filling stages and introducing new pests or diseases

That waning scent

“When that brown‑rice cooked, I used to carry it over to my neighbours. It was like sharing perfume. Now even the E‑chhum grows faint, and we don’t smell it,” recalls Chencho of Geptey.

Like Chencho Passa Gyem said, “The farmers here always said cooking can wake the whole neighborhood. But now, “the rice cooks—it smells only of water.”

Other farmers across Gewogs echo similar sorrow. One elder of Talo Gewog reports his own rice yield remains stable—2.3 t/acre from HYV—but he too laments the absence of taste and fragrance.

Sangay Tshomo (from Trashi Yangtse district) speaks of delayed transplanting and yield loss when rains fall during harvest: “The grain spoils before it even matures,” she says

Though her region is not Paro, her concern is common: the quality of rice is imperiled.

The anatomy of aroma loss

Scientists and veteran farmers trace the aroma loss to several intertwined causes.

The use of excessive agrochemicals and over‑application of urea and herbicide butachlor which, they say, can degrade soil microbial communities responsible for producing aromatic compounds during rice development

Further, HYV seeds are bred for rapid growth, often sacrificing the slow aromatic compound buildup found in native varieties.

As farmers lose aroma, they still aim to preserve yields to feed families and earn income. In Paro, most fields now plant HYV irrigated rice to maintain 2.3–2.4 t/acre, higher than the national averages while many districts only reach1.1–1.4 t/acre.

A grain of hope

In Paro, rice is not just nutrition, but is part of social life, festivals, and ancestral memory. Without its aroma, natives say, home-cooked rice feels empty. A Lango elder tells of family gatherings when cooking E‑chhum was itself the ritual and the scent the invitation.

That cultural loss intersects with economic hardship as foreign rice imports grow, Bhutan loses more than aroma but loses autonomy and identity.

While, climate variability stresses grain formation and opens door to pests and erratic rainfall, chemical dependency degrades soil, harms aromatic compounds.

Further, labor and land scarcity make replanting old landraces economically unfeasible.

“It is a microcosm of a larger crisis. In Bhutan’s rice‑growing districts, climate change, food security and cultural preservation collide, says an agri expert based in Paro.

A last whiff

Walking through a field in Geptey this July, Chencho bends to feel the grain in his palm. “It’s heavy and the yield seems good,” he says. But when he later cooks those grains, sitting by his ear, he listens, unconvinced.

He stirs the rice and pauses, remembering the scent that once greeted him across the valley. What he fears most is that his grandchildren grow up never knowing that smell.

Paro’s rice fields still glisten green through monsoon and sunshine. But as clouds drift over the terraced paddies, they seem like blank pages waiting for a story that may never be told again.

Unless action, and patience, allow aroma to return to those fields. Once again.