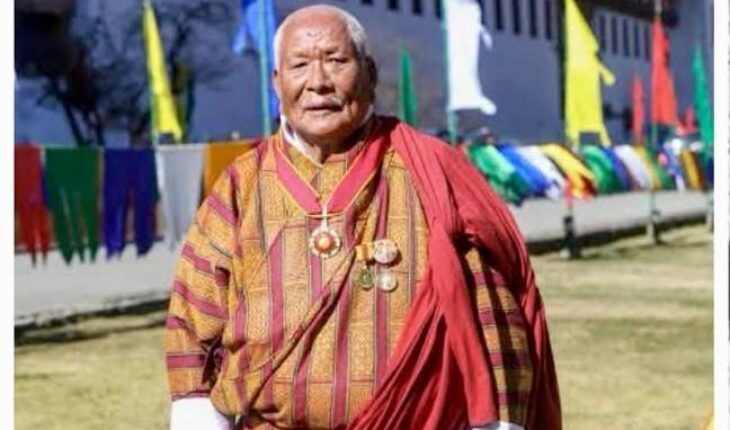

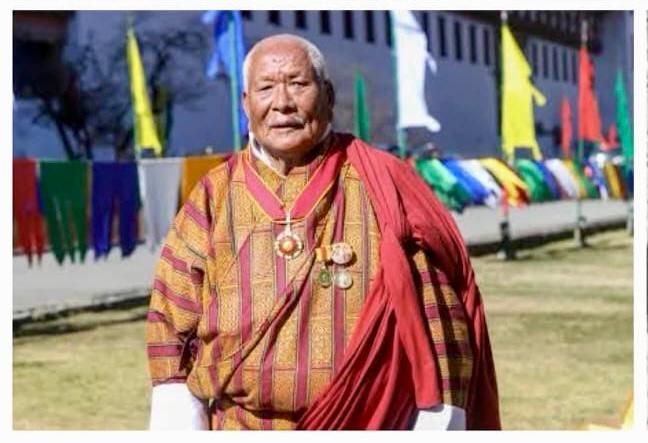

There was something uniquely awe-inspiring and supremely edifying about the person and presence of the giant figure who came to teach us, fresh university graduates from different institutions in India and beyond, the essential elements of the country’s traditional etiquettes commonly called Driglam Namzhag. He didn’t introduce himself to us but went about the task at hand right-away. As the course progressed, we came to know that he was the Gyalpoi Zimpoen, the Royal Chamberlain to His Majesty the King.

My very first impression of our Driglam Namzhag Lopon, as most of my peers would refer to him as, was that here was more of a gracious father-figure rather than an austere instructor of manners and mannerisms, do’s and don’ts, right and wrong. I found here a large-hearted, non-judgmental, pure soul who stretched out his arms to welcome home, to embrace and to reintegrate this restless group of graduates who had travelled far and wide, physically and psychologically, into the inner fold of our country’s national consciousness.

Dasho Dorji Gyeltshen’s assistant would have already placed all the essential items in the hall for our training including brooms, serving items and utensils to begin at the most basic level. But Dasho would say: “You are all educated people and will be in important roles. So, you don’t have to go through this elementary training like learning to sweep the floor or to serve tea even though these experiences would ground an individual with important life-skills.”

Thus, our training would mainly be focussed on learning the essentials of conducting oneself in different settings, in front of various levels of dignitaries and elders, positioning and presenting onself in the presence of authority figures, observing correct protocols as required by different situations, use of kabney and rachu, offering courtesies accompanied by ceremonial khadars, being mindful of the need to moderate the volume of one’s speech, elegance and speed of sitting down and getting up, holding eating utensils and degree of exposure in the act of eating and drinking, the relative length laagey for different levels of wearers, the reach of the lower end of the gho, manner of entering and exiting the room, taking a peek from the side of the door-curtain, improvising a substitute for a forgotten kabney or rachu, manner of walking and sound of footfalls, giving way to people in authority and elders in the event of a sudden encounter, protocol on approach to and entry into dzongs and monasteries, cultural nuances, protocols surrounding the national flag and the national anthem as well as other symbols, reverence for the golden throne and national institutions, citizenship obligations, among various other important lessons of personal and national significance.

It didn’t take long for us to discover that behind these apparently ordinary activities, there was an inherent, unspoken, but all-permeating principle of harmony and balance that distinguished the desirable and the deviant as a function of one’s character and cultural sensitivity as a member of the society. As the pre-eminent authority on and passionate upholder of Bhutan’s rich culture and hallowed traditions, Dasho Zimpoen drew home to us the crucial need to imbibe and understand the obvious and subtle nuances of the country’s timeless heritage and cultural treasures that give to the country its uniqueness, its self-respect, integrity and honour.

There is an order of personal conduct that could be either in alignment with the national ethos or at variance from it. And, the greater the distance between the accepted norm and individual conduct, the bigger the risk of the unravelling of the system over time. The peerless heart-son of Bhutan knew better than anybody else that it falls on succeeding generations of Bhutanese citizens to receive the wisdom and practices of the past as a matter of individual right and of personal responsibility in the larger interest of the country.

Today, when I talk about the two important qualities of an educated person – usefulness and gracefulness – I can immediately relate them to the subtle ways in which these virtues were embedded in our Driglam Namzhag classes by our inimitable Lopon during that critical phase of our life when we needed to be anchored to the core values of our country. Looking back at those sessions, I consider myself truly fortunate to have been able to receive such important lessons to guide our personal as well as public life.

Dasho Dorji Gyeltshen embodied the true essence of Drig – harmony, proportion, coherence, unity… – and Lam – the way to achieve these essential attributes – and Namzhag – constituting a whole body of personal and social virtues that govern good life, and by extension, the integrating elements that make strong nations. The idea of outer behaviour and inner virtues, the coming together of the role and soul, the balance of the physical and the spiritual is germane to the notion of a harmonious and peaceful society.

The endearing grace, the edifying elegance, the effortless flourish with which Dasho Zimpoen conducted each act of our training was in abundant display at all big national events when he oversaw important ceremonies to mark great events and significant occasions. What I learnt from our revered fountain of our cultural wisdom as a fresh university graduate more than forty years ago has stood me in good stead all through my public service and personal life.

Dasho Zimpoen would often visit Sherubtse College during the royal entourage of His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck and spend several days on campus overseeing the preparations for important audiences to the college community or in connection with the Five Year Plan discussions with the public. I was always struck by the level of personal discipline, inexhaustible stamina, and meticulous attention to the minutest detail.

I had the rare privilege of working closely with Dasho Dorji Gyeltshen over several days, for extended hours, on many occasions. I would request Dasho to take a break and have some rest but he would instead ask the younger me to have a breather. It was then I discovered the exceptional exemplar of personal integrity and dedication that the extraordinary Royal Chamberlain was in every sense of the term. Hunger, thirst, exhaustion mattered little when it came to working to perfection to welcome The King.

When I came to Thimphu, I had more frequent opportunities to meet Dasho Zimpoen and to receive his kind affirmations of my own sense of loyalty and work-ethics. And, whenever I collected courage to submit a call to the revered Royal Chamberlain, he would recognise my voice right-away and respond: Oie Lopon Chhenpo, gadey bey zhuie go! I will miss this caring voice and my unfailing well-wisher and precious source of strength…

It was Bhutan’s good fortune that we had a wise fatherly figure like Zimpoen Dorji Gyeltshen to take care of the well-being of a young prince who was called upon to take on the monumental responsibility of the King, almost overnight. Our beloved Drukgyal Zhipa had the unfailing personal support and emotional reassurance provided by the singularly trusted and devoted servant during the most delicate period in the life of our young King and throughout the reign of our Great Fourth and beyond, spanning 61 long years.

As a grateful nation bids farewell to one of its most precious jewels, we witness the end of an era. We are the poorer off by the loss of an irreplaceable repository of Druk Yul’s cultural heritage, a true embodiment of grace and humility, the ultimate image of integrity and service, a rare icon who shone in our celestial firmament as our North Star. With malice towards none and goodwill for all, here was a legend, an institution, and a patriot who enshrined the nation in the deepest recesses of his soul and kept undimmed vigil throughout.

May the priceless legacy of this precious Heart-Son of Bhutan continue to inspire succeeding generations of royal courtiers and citizens as we strive to hamonise our role with its soul…

Gratitude and prayers forever…

Thakur S Powdyel

Former Minister of Education.